"I came to this country to save my life."

High on a hill and up a steep driveway sits a small building overlooking Spring Valley in San Diego County. Through a sliding screen door and into an office, people race by, dodging piles of donated clothing and stacks of folding chairs. This is the headquarters of the Minority Humanitarian Foundation (MHF), a nonprofit organization founded by Mark Lane to provide relief efforts to migrants and asylum seekers at the San Diego border.

Mark and MHF team member Jules Kramer sit in their office, half-hidden under stacks of paperwork (mostly asylum packets) and handmade thank-you cards—mementos of gratitude for the work they do, often without pay or sleep, simply “because we can.” MHF is run by Jules and Mark, with the help of volunteers, and it’s a bootstrapped operation working simply to offer what has been most absent during these immigrants’ long journeys: basic humanity.

01.

Jules takes a call from an asylum-seeker who was just released

02.

Mark describes his tattoo, “It’s from Batman—‘Die a hero, before you become the villain.’”

03.

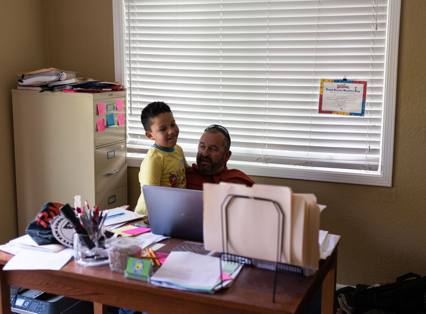

Mark takes a moment to talk to his son in the MHF office

01.

01.

03.

03.

02.

02.

Jules“We know we’re only affecting a very, very small percentage of people, but we’re just trying to make the biggest impact we can.

Every day thousands of asylum-seeking migrants wait in makeshift shelters in Tijuana, holding their places in line for processing at a US detention center. But, each day, only a few dozen are called, a process slowed by never-ending administrative roadblocks. All the while, at seemingly every advance: more waiting. Waiting to arrive, waiting in shelters, waiting in lines, waiting for numbers to be called, waiting for answers.

If called for processing, migrants enter a cold, crowded cell for days, weeks, sometimes months, as US officials decide whether they will be tagged with an ankle bracelet and granted temporary entry or deported back to their home countries. If granted parole in the United States, these legal immigrants are typically released along a road in San Diego without any money in hand or the opportunity to make a phone call. Their paperwork is written in English, making it difficult to understand, and they are given no direction as to where to go next.

Amidst that uncertainty, Mark and Jules help ground them, providing basics during these vulnerable moments of transition, their very first moments in the United States.

01.

Mark and Jules pick-up supplies for a donation run

02.

Jules loads supplies at the MHF storage facility

03.

Jules preparing for the next supplies drop-off.

01.

01.

03.

03.

02.

02.

Mark“You walk up to some very scared people. They don’t know what to do. We immediately find out: ‘What do you need right now?’ It’s almost always food and a shower. It’s really simple.

From minute to minute, Mark and Jules respond to calls from migrants in need; provide food, clothes, and temporary housing; and coordinate transportation. They dispatch Lyft rides to meet those left at the border (Mark himself is a Lyft driver, too) or they themselves will wait roadside for hours when they know a dropoff is likely to happen. They act at a pace akin to emergency medical technicians—only they must be the dispatchers, the medics, the hospitals, and the rehabilitation programming all in one. And their work begins before the migrants even land on US soil.

Jules, her green hair tied back in a ponytail, watches out the window as the rubbled streets of Tijuana pass by. Beyond the window is Friendship Park, on the vibrant, colorful Mexican side of the border wall. It’s muraled and lined with gardens and orchestral mariachi bands—a stark contrast to the near-sterile San Diego visible through the bars. Back in the car, the seats behind Jules are loaded with diapers, feminine-hygiene products, clothes, toys, and other relief supplies the foundation brings to shelters on a tri-weekly basis.

01.

Tents are arranged at the migrant shelter as a makeshift sleeping area.

02.

Migrants wait in line for food from the shelter kitchen.

03.

Laundry hanging to dry in the afternoon sun outside the shelter.

01.

01.

03.

03.

02.

02.

Jules“They just walked across a continent, they left everything they knew, and now they’re in purgatory just waiting for their number to be called.

Deeper into Tijuana at the Movimiento Juventud 2000 shelter, some one hundred people crowd into a small aluminum structure. These are asylum seekers, waiting their turn. They fill the space, eating, talking, passing the time. Parents hold their children, wash clothes, cook. Kids play tag. Conditions are dire—people sleep in tents or on stained mattresses, and some individuals are covered with visible rashes and pox—but the energy is a patient one. Many migrants still prefer passing time in these shelters to living with the dangers that came before,and many will wait for months while following the prescribed order of events for seeking asylum in the United States.

01.

Jules visits Tijuana shelters.00:00

Jules“If they miss their number being called, they have to get a new number. It all starts all over again.

While in the shelters, they’re waiting for their number in line to be called—a system known among migrants as “the lottery.” It’s a handwritten book kept by Mexican immigration authorities that lists which asylum seekers will be handed over to US Citizenship and Immigration Services for processing each day.

Jules unloads the supplies from her car. She’s all business here: engaging with new and familiar faces, handing out business cards, making eye contact, smiling: basic acts to begin the process of dignifying and humanizing this migrant community. “We give people our business cards who are going to be processing and tell them, ‘Call us when you get released. Call us.’”

Oscar, a man in his thirties, squints as he steps into the sunlight outside the fast food chain where he’s spent his first hours in the United States. He was released from a US detention center without assistance or instruction, so he called Mark and Jules.

Oscar holds the hand of his six-year-old daughter. Around his ankle is a GPS-monitored electronic bracelet which he must keep charged until his case is decided. Trailing them is his wife, also tagged with an electronic bracelet. In her arms is their six-month-old baby, who scans the new terrain from her mother’s hip.

01.

After leaving the detention center, a family calls Mark and Jules for assistance.

02.

After leaving the detention center, asylum-seekers must wear an ankle bracelet at all times until their court date.

01.

01.

02.

02.

Oscar“I thank God that we got on this side. Now my daughters will have a future.

02.

Mark and Jules respond to a call that a family was released at the border.

00:00

For the last two days, inside detention, Oscar was separated from his wife and daughters and placed in an all-male holding cell. Occupants dubbed it the “Ice Box” because of its frigid, windowless conditions.

Less than an hour after receiving Oscar’s phone call, Mark and Jules—who met him on a donations run on the other side of the border—are checking him and his family into a nearby motel. Mark explains to Oscar how to use the shower and lights, while Jules works on reuniting them with friends across the US. She gets help from Miles4Migrants, a nonprofit organization that uses donated frequent flyer miles to reunite refugees with families.

Oscar’s six-year-old is excitedly chattering about the pool across the parking lot, and the baby is laughing at whatever babies laugh at. Even now, they feel just a little more human.

01.

The family takes a moment to breathe as they settle into their motel room.

02.

Oscar and his wife are relieved that their children are safe.

01.

01.

02.

02.

He touches his ankle bracelet. “It would seem this is only worn by people that have problems with the law,” he says, “but it’s also proof that I didn’t come violating the laws of this country, that I want to do things right.”

03.

In their hotel room, the family tells us about their experience.00:00

Mark“They’re going through a process that’s legal. We should treat them like human beings.

Tomorrow they plan to fly out, and they’ll be one day closer to their first court date, likely to be followed by several more court dates. Eventually, they will learn whether they can stay. Eventually. The process can take up to three years.

Oscar knows they’re lucky to have friends in the United States, lucky to have a place to fly to and wait out the uncertain asylum process. And, for tonight at least, they’re not out on the street. He and his wife sleep close to the outlet to charge their ankle bracelets. But they’re together, and they’re safe.

It’s 2:15 p.m. on a school day, and Honduran asylum seeker Mari waits for her teenage son Javi outside an elementary school in San Diego. After landing with the caravan in Tijuana, they were able to gain parole in the United States. But without anyone to receive them, Mari and Javi, who has Down’s syndrome, have remained in a homestay in San Diego for the last seven months.

01.

Mari and Javi's close bond helps them survive the waiting.

02.

Mari picks up her son, Javi, from the elementary school he's been attending since arriving in San Diego.

01.

01.

02.

02.

Mari“I don’t have family here. I don’t have anyone. I felt very good because my son was going to get treated by doctors, but I was afraid because I didn’t have anywhere to go.

Javi turns the corner and beams upon seeing his mom. He kisses her cheek and proudly sings her the alphabet, while Mari, glowing, sweeps the hair from his eyes.

“In Honduras there’s no school for these children,” she says. “They never accepted my son at school because of the problem that he has, but he wanted to study very much. And that’s why I risked my life to come where I am now.”

Mari isn’t exaggerating when she speaks about threats to her life. “I remember helping Mari unpack, and the last thing was this folder,” says Jules. “And it was a folder full of different pictures of her dead relatives in their caskets. Like, this is her whole family and they’re dead and now she’s in this country. She has a son with Down’s syndrome and she’s doing the best she can.”

01.

Mari in the bedroom where she is staying with her son, Javi.

02.

An interminable waiting is part of the experience for asylum-seekers.

01.

01.

02.

02.

To Mari, her best means finding work and securing an apartment for her and Javi. Asylum seekers are eligible for work permits six months from the date they turn in their petition for asylum at their first court date, which sometimes takes months to arraign.

And while Mari and Javi enjoy the first months of his education, the future is unresolved. Like the others, they still must wait to see if they will be granted asylum in the United States. If rejected, they’ll be sent back to Honduras, to what’s left of a home.

Jose Galvan immigrated with his parents from Mexico twenty-three years ago. He has lived in San Diego since he was two years old; he is a theater director, an artist, a Lyft driver, and a Deferred Action for Childhood Arrival (DACA) recipient. He’s the first in his family to graduate college. And though his DACA status allows him and other so-called “Dreamers” to stay without threat of deportation, recipients must reapply every two years.

“It has become a part of my everyday life,” he says. “No new applicants can apply for the program, but anybody under the program is able to still renew. That’s hundreds of thousands of people who still have protection. But that can change any moment.”

01.

Jose walks through the hills overlooking San Diego.

02.

For DACA recipients like Jose, the future is uncertain.

01.

01.

02.

02.

The fee to reapply for DACA status is $495 each time. And even for Dreamers, there is no path to citizenship, or even legal permanent residence. Before the DACA program began in 2012, there was no way to turn academic success into something more. No social security number meant no driver’s license or any other form of legal identification. No legal identification meant no real employment prospects. These adults who had been brought to the United States as children were forced into a state of impermanence and hiding.

04.

Jose shares his perspective as an American and a DACA recipient.

00:00

Jose“This country was founded on this idea of the American dream, that anybody can make something better for themselves. But it’s becoming a more narrow scope of, like, ‘Well, who was the American dream actually for?

Even stuck in the in-between, Jose and his family refuse to stop pushing forward with even a compromised American dream. “My brother graduated college just a few weeks ago,” he says. “He’s the second in our family to do so. We’re starting a legacy of higher education and so we’re showing that we are capable given the opportunity. Many people are not given that opportunity."

For many immigrants in America, the opportunity to build a secure home can feel continually just beyond reach, even when following all the right steps.

It’s been days now since Oscar and his family first stepped into America. They have been shuffled between motels and host homes after their flight was repeatedly cancelled due to weather.

01.

Jules picks-up the family for their flight.

02.

Oscar finishes packing before the family heads to the airport.

03.

The family's journey continues.

01.

01.

03.

03.

02.

02.

“In 2018, 65 percent of those seeking asylum in the United States were denied entry, and sent back to the conditions to which they came. The public is still waiting on the numbers for 2019.

They’re trying again to fly. Jules rides by their side to the airport; for most who take this trip, it will be their first time on a plane. She helps the family check in and walks them through security and up to the boarding area. Then she says goodbye.

“We don’t know what’s going to happen after this,” says Jules, pausing to reflect. “Mark and I are two people just scrambling like chickens with our heads cut off trying to save the world. We know we’re only affecting a very, very small percentage of people, but we’re just trying to make the biggest impact we can with those people.”

Then Jules is back on her phone, arranging to meet a young woman who may be dropped off by bus late at night on the side of the road in San Diego. She doesn’t want the woman to have to wait alone.

For Oscar and his family, for Mari and Javi, for Jose, and for thousands of others, the wait to stay continues.

Every issue contributing to our current immigration crisis is interconnected. Your stories inspire us to continue to take a stand — when our community of riders and drivers is threatened, we’re encouraged to take action.

To help protect the rights of asylum-seeking refugees in the United States, we are humbled to support the Minority Humanitarian Foundation, led by Mark and Jules featured in this story. MHF provides a humanitarian response to asylum-seeking refugees through on-the-ground relief efforts and more.

Please join us in supporting them.